“I disapprove of epiphanies and their phony auras but I am besotted by them — can’t get enough of them in life or elsewhere. So sue me. Seriously though, as a person who was brought up with religious faith and then got out of it, I’m always looking for secular manifestations of the sacred.” Charles Baxter

I wrote a paper on John 2 this past semester, and in his feedback my professor noted that the water into wine story is part of the lectionary reading for the feast of Epiphany. He thought this was an interesting connection between the story itself and the idea of epiphanies in literature.

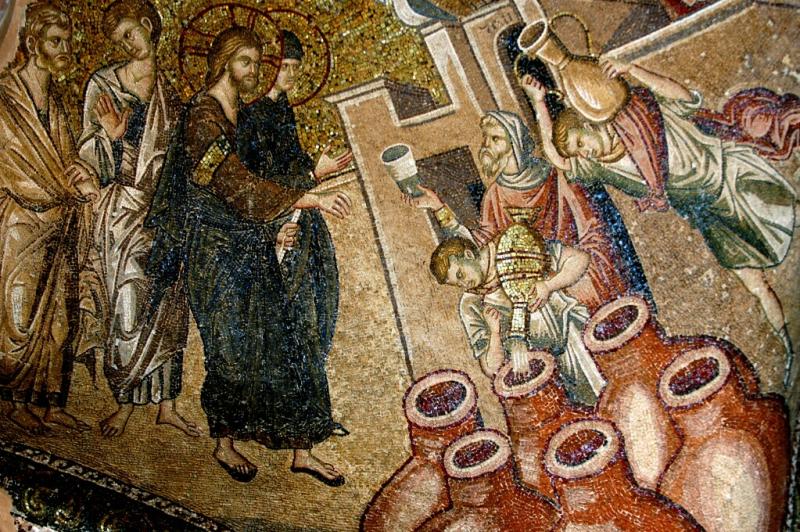

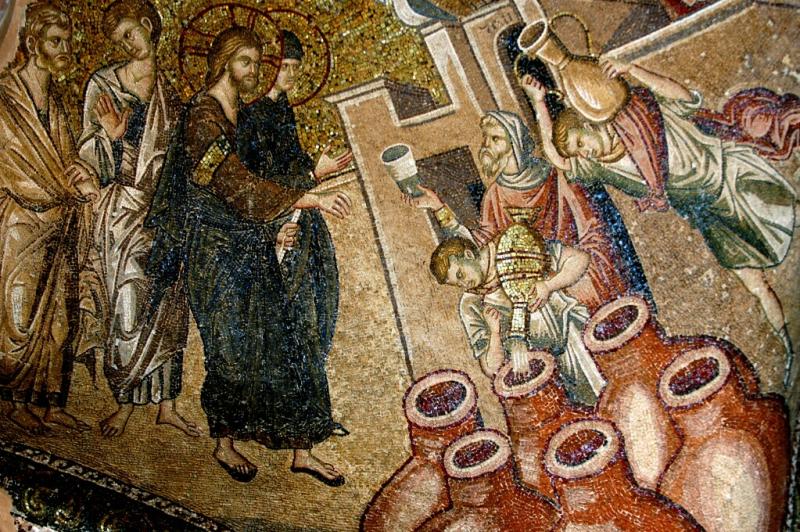

Indeed it is an interesting connection. And I got to thinking about it and reading up on it, and it turns out the epiphany has fallen on hard times. The epiphany in it’s truest form comes from Greek Mythology. Gods and goddesses break into the human realm, and people are overcome with the presence of the divine. In the Bible the epiphany is more properly called a theophany or christophany. Think of the burning bush. Think of Jacob wrestling the angel. Think of the Mount of Transfiguration. Think of the Ascension. The Bible is so thick with epiphany that it is almost commonplace. Indeed, the Bible is an ever increasing cascade of epiphany culminating finally in the eternal epiphany of God dwelling with his people (Rev. 21:3). What is interesting is that n both the Greek and Christian understandings, the epiphany’s center of gravity is the divine. The human’s experience is one of revelation. It is not experience, in other words, that comes from within, but from without.

But epiphanies are very different in literature, and we have James Joyce to thank for that. He was the fist to self-consciously use epiphany as a literary term. For him the epiphany was, a “sudden and momentary showing forth or disclosure of one’s authentic inner self.” It was a way to describe a particular moment of clarity, usually towards the end of a story, that characters have about themselves and their lives. (To see a beautiful example of this read Joyce’s story “The Dead.”) Typically, if and when we say we’ve had an epiphany, we mean it in this way. With Joyce the moment of divine encounter became a moment of personal clarity. The center of gravity shifted from the divine to the self.

So why would a writer like Charles Baxter hate epiphanies and write an essay called “Against Epiphanies?” I suspect that Baxter senses on some level that the epiphany as Joyce describes it is a sham. If there is the possibility of revelation or the divine, the epiphany seems inevitable. If there is a voice on the other side, we would, it seems, in moments of clarity, distress, comfort, euphoria, in those moments, that is to say, where we come to the edges of human experience, hear that voice or encounter the divine. But in a voiceless world, the epiphany first becomes a “secular manifestation of the sacred,” and eventually, disintegrates because in our world the self is so incoherent that any moment of inner clarity would only reveal a sliver of a fragmented whole. For us truly postmoderns there is no authentic inner self to be revealed.

Without a true sense of the divine and without a coherent self, the literary epiphany becomes, as Baxter says, “phony.” Life, he insists, isn’t like that, since if epiphanies happen at all, they happen rarely. And yet he still longs for them. His self-contradictory impulses reveal an appetite for transcendence, for the divine, for there to be a voice on the other side. But contemporary literature has no space for the divine, no category for the possibility of revelation.

Despite these tensions, you don’t have to look far in contemporary literature to find epiphanies. Take Jonathan Franzen’s novel Freedom. This scene towards the end of the novel records the reunion of Patty and Walter Berglund, who had been estranged by adultery and betrayal:

Her eyes weren’t blinking. There was still something almost dead in them, something very far away. She seemed to be seeing all the way through to the back of him and beyond, out into the cold space of the future in which they would both soon be dead, out into the nothingness that Lalitha and his mother and his father had already passed into, and yet she was looking straight into his eyes, and he could feel her getting warmer by the minute. And so he stopped looking at her eyes and started looking into them, returning their look before it was too late, before this connection between life and what came after life was lost, and let her see all the vileness inside him, all the hatreds of two thousand solitary nights, while the two of them were still in touch with the void in the sum of everything they’d ever said or done, every pain they’d inflicted, every joy they’d shared, would weigh less than the smallest feather on the wind.

Here is epiphany in the Joycean sense—a moment of clarity and closure. And perhaps even of forgiveness and reconciliation. But what does it amount to? Two estranged characters reconnect and in their connection see past themselves into what lies beyond them and what lies beyond them is nothing. This is an epiphany, yes, because the characters come to see some truth about the world but it is an epiphany without transcendence. There is no voice, only void. And if in the end both joy and sorrow weigh less than the smallest feather on the wind, then what use is either?

So where does this all leave us? When I think of epiphanies in any sense it becomes clear to me that I ought to be wary of my own capacity for insight. I ought to be suspicious of my own sense of clarity. I am waiting for the world to act on me, to arrange itself in scrutable ways. Art is a path to such clarity, but as a Christian I sense that this is only true because there is a voice on the other side. To be an artist is to have an appetite for transcendence, and yet, in what seems to me to be the height of irony, many artists reveal that appetite in their longings for epiphany but refuse it’s true nature by denying what an epiphany really means—that the divine seeps into the world, that there are moments when we see behind the curtain and what we see is not the void, but something almost more horrifying (if we are really honest). We see the terror of God’s beauty, a beauty that exposes ugliness and strips pretense. And though we might walk away with our faces shining like Moses, we are first disintegrated like Isaiah.

Unless.

Unless that God comes to us in our form, and spends his days as a human gradually unfolding his glory, a kind of epiphany by degrees. Read the Gospel of John with that in mind—“And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth.” Each of his signs points to his glory, and for those with eyes to see he is the epiphany of epiphanies, the theophanies of theophanies. He is the first and final word who gives all other insights their meaning. He is our assurance that when the world becomes transparent to us, what we see on the other side is not void but the vast abundance.