The magnificent Vatican II document devoted to divine revelation and to Holy Scripture, Dei Verbum, called the Roman Catholic Church back to a living encounter with the word of God written. In his book Praying the Bible: An Introduction to Lectio Divinia, Mariano Magrassi argues that the practice of lectio divina, praying the Bible itself, is critical to that recovery. For the church from the beginning has prayed the Bible, meditated on the Bible, and in the language of of the prayer book has always sought to “read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest” the words of Holy Scripture. Magrassi wields wide learning and deep reading of the Fathers and the Medieval Monastics to demonstrate that in its periods of greatest fruitfulness, the Church has prayed the Scriptures, not just studied the Scriptures.

If only for the treasure trove of quotes from the span of the tradition, this would be a book worth owning and returning to. But the book is much more than a patchwork of quotations, because Magrassi writes not from the detached standpoint of a scholar merely accounting for a phenomenon he observes called Lectio Divinia. He writes as one who prays the Scriptures himself. And so he works to reconcile a divorce he laments—that “between piety and exegesis” (56).

Here Magrassi describes what might be gained from the approach to Scripture he commends:

“The chief values to be reclaimed seem to be these: a living and coherent faith in the transcendence of God’s Word; a sense of Scripture’s infinite fruitfulness and inexhaustible riches; a deep admiration for the biblical world where beauty is a reflection of God’s face and truth a foretaste of the vision toward which he is leading us, a profound sense of the unity of Scripture, so that everything is seen as a single, vast parabola, one great sacrament of the Christian realities; above all, a way to read it as a Word that is present and puts me in dialogue with the God who is living and present; an ease in translating reading into prayer and using it to shed light on questions of existence in order to model my life on it; that presence of all my soul’s listening faculties which Claudel refers to when he write: ‘I take the Word to the letter. I believe one God who swears by himself. God is Act, and all that he says forever is forever actuality’” (13).

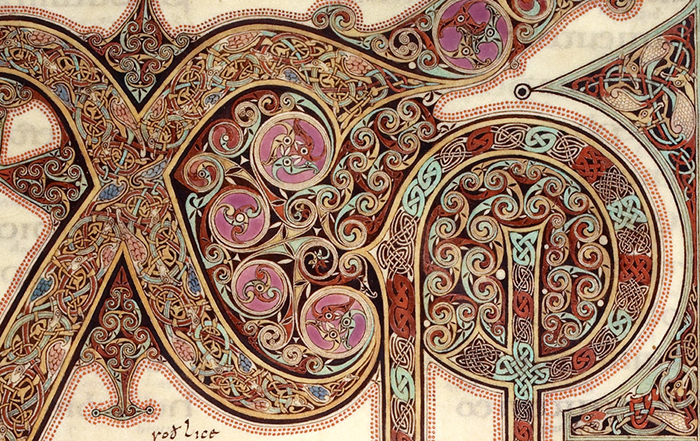

As I read my mind kept coming back to the image of the illuminated page, the image of a monk bent over vellum, carefully penning words and adorning them, laying out gold and other precious materials so that the page might glow. The illuminated manuscript is more than an artifact of a bygone era but a kind of living symbol of a way of reading, approaching, even adoring the word of God. God’s words are precious, lively, and luminous, and so those charged with the sacred task of preserving those words believed that the word was a means of illumination. It is no wonder then that their decorated pages aspired to radiate the light of the word.

The illuminated word also draws to mind the lightness of light, its potential for joyful playfulness. While encountering God is always a weighty matter (God’s glory is his weightiness, after all), there is a lightness too, something like the playful dance of lover and beloved. Lectio Divina sometimes light, sometimes weighty like the language of lovers, a language which moves between the poles of surplus and silence. At times words pour forth in poetic abundance, while at other times, both must fall silent in reverent awe.