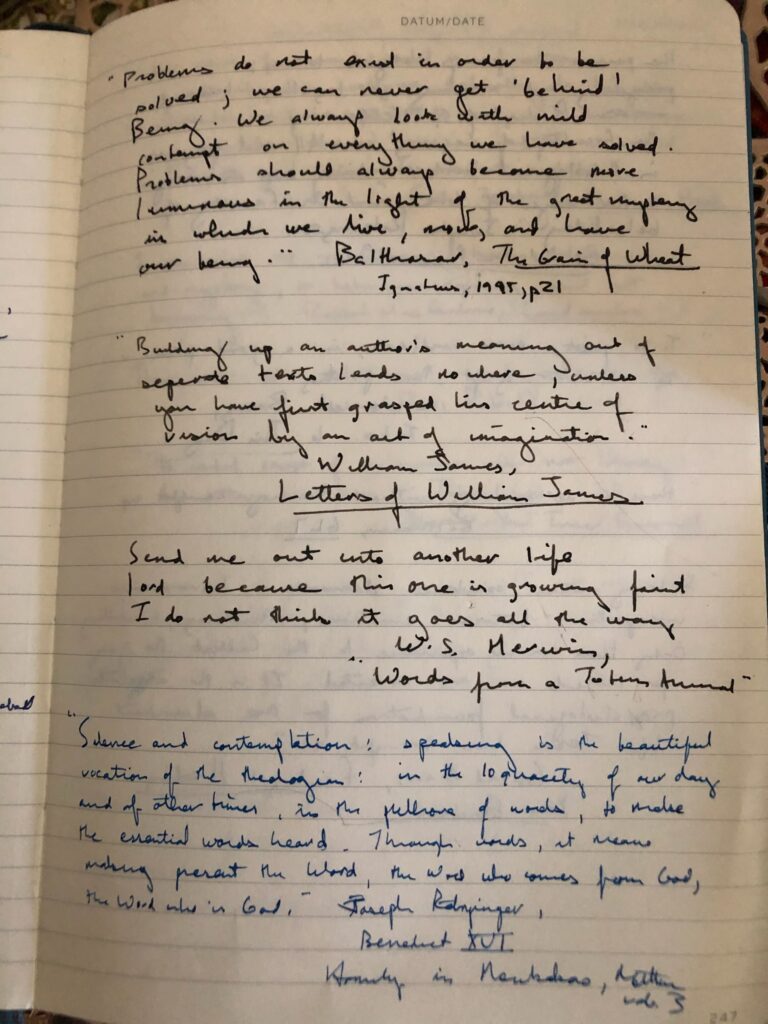

One of my English professors in college had us keep a commonplace book where we wrote down important quotations, interesting images, central ideas, etc. from the things we were reading. It’s a practice I’ve more or less maintained since college, and when I taught high school English, I had my students keep a commonplace book as well.

A commonplace book is like a travelogue of the mind or a kind of map for the ideas and images that have served as landmarks. Mapping the world in this way is not an attempt at mastery but a desire for orientation, the desire to see what can be seen, to know what can be known in a lifetime, while recognizing the limitations of a single person to map the world in any comprehensive way. Loren Eisley reminds us of this with his striking image of the human journey in time and the desire for knowledge as a kind of caravan:

“We have joined the caravan, you might say, at a certain point; we will travel as far as we can, but cannot in a lifetime see all that we would like to see or learn all we hunger to know.” Loren Eisley, The Immense Journey

I recently filled up a notebook, so I thought I would collect some of my commonplace quotations here that dealt with similar themes. One benefit of keeping a commonplace book is the ability to review the themes and preoccupations that emerge over a period of time. As a preacher and teacher of scripture and as a student of theology, one perennial theme for me is the need for intellectual modesty and humility. Every intellectual pursuit has temptations and presumptions, but presuming to speak for and about God might be the biggest presumption of all. And yet as Pope Benedict XVI notes, it is the vocation of the theologian to speak, but before speaking one must listen:

“Silence and contemplation: speaking is the beautiful vocation of the theologian: in the loquacity of our day and of other times, in the plethora words, to make the essential words hear. Through words, it means making present the Word, the Word who comes from God, the Word who is God.“

The theologian speaks the word of God, but the theologian must first hear the Word and then speak. Theology then begins in contemplation, with closed lips and open ears. But the theologian does not stay silent. There are words to speak precisely because there is a Word who has spoken. There is a Word that has made and that even now upholds all things. There is a Logos that makes the -ology of theology not only possible but vital.

Such an approach to theology, one that begins in silence and then speaks, guards against two dangers. On the one hand, there is the danger of hubris, the delusion that in saying true things about God that we have said everything about God. On the other hand, there is the danger of paralyzing agnosticism. It is a kind of fear to say anything about God since it is impossible to say everything about God. Though this fear might masquerade as humility, real humility and silence in the face of mystery do not result in an agnostic throwing up of the hands or in a despairing resignation, but in a desire to more deeply indwell the mystery and then to speak truly of it.

Naming and knowing can be forms of appreciation and can be real knowledge, even if they are not comprehension and mastery. As Robert McFarlane says, “I perceive no opposition between precision and mystery, or between naming and not knowing.” Robert McFarlane, Landmarks

And mastery itself is the wrong goal. As Balthasar reminds us, “Problems do not exist in order to be solved; we can never get ‘behind’ Being. We always look with mild contempt on everything we have solved. Problems should become more luminous in the light of the great mystery in which we live, move, and have our being.” Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Grain of Wheat

Moreover, the God we speak of is love, and so we know him truly by loving him. “The person who prays begins to see: praying and seeing go together because—as Richard of St. Victor says—‘Love is the faculty of seeing’…All real progress in theological understanding has its origin in the eye of love and its faculty of beholding. “ Joseph Ratzinger, Beholding the Pierced One

In sum, what begins in silence ends in praise. Praise and thanksgiving are the fruit of true theological reflection.