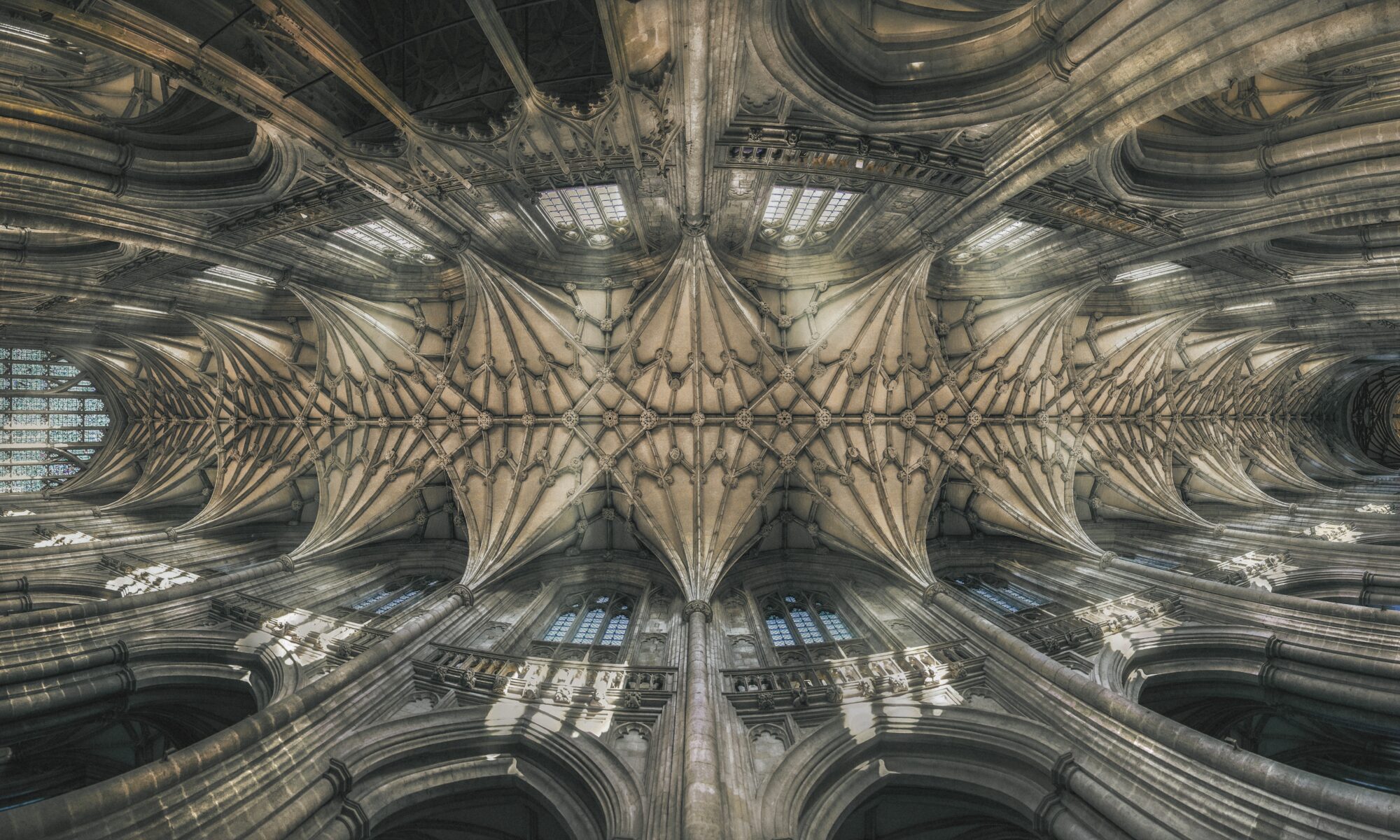

Having recently posted about theology as architecture, I was struck by this passage about mystical theology from theologian Denys Turner. In explaining the mutual interplay of positive (cataphatic) and negative (apophatic) theology, he employs this striking architectural metaphor:

“What falls short of God is language, the whole cathedral of speech, formed at once of presenting mass and absenting space, neither of affirming mass without the space it encloses, nor of negating space without the enclosing mass—for without both at once there is no shape, no architecture; and it is only the distinctive form of their conjunction that we possess the transcending mystery of Cuthbert’s place in Durham or Abbot Suger’s at St. Denis in Paris.” Denys Turner, God, Mystery, & Mystification

Turner has done important work on mystical theology and on negative theology in general, especially in his book The Darkness of God. Given his work in negative or apophatic theology (which is generally mystical), what he has to say about the necessity of both positive and negative theology is worth paying attention to. There is a great tendency to privilege one form other the other, to use one to negate the other but because positive and negative theology do not cancel each other out, because both cataphatic and apophatic theology mutually inform each other, because the cathedral of language about God depends on both, it will not do to privilege one over the other or to exclude one for the sake of the other. To do so might bring the whole building down. Or as Turner has it, if one insists on only the positive, the cataphatic, then one will end up with nothing but “affirming mass”. And if one insists on only the negative, the apophatic, then one will end up with nothing but “negating space.”

Importantly, the cathedral he imagines is a cathedral of language, and it is language itself that falls short of God, including the absence of language or the negating language of negative theology. In other words, one cannot appeal to negative theology as an escape from the thorny problem of how we speak about God, and this to my mind has important implications for the on the street, or the in the pew, understanding of mystical theology which might see mystical theology (negative theology) as an escape from the language problem.

In my work as a pastor, I have seen that there is an appetite for mysticism among many disaffected Evangelicals, and for the negative theology that so often goes with mysticism. The attraction is not without merit, and I am personally not surprised that I have pastoral conversations about The Cloud of Unknowing. I acknowledge the possibility of a confirmation bias, since many who come to Anglicanism do so with an inchoate and intuitive attraction to mystery. Nevertheless, many disaffected evangelicals have felt crushed by the “affirming mass” of nothing but positive theology, and they have found some room to breathe, as it were, with negative theology. But as we make space for the negative, for the mystical, the danger becomes opening up into nothing but the void.

In accepting that language is a limitation, theologians are not admitting defeat, rather they are affirming what is and in the best cases accepting the limitations of being human. But this is no cause for despair. That we speak of God at all is astonishing, but our speaking is merely a response to an even greater astonishment—God spoke first. Yes, as Calvin has it, God’s words to us are a kind of baby talk, which is nonetheless still communication and therefore meaningful because as all baby talk, it is spoken to us in love.

Can we hear this word of love? It depends greatly on whether or not we can be quiet. For it is only in silence that we might hear the Word spoken to us.

As Fr. Stephen Freeman beautiful writes in his post “Words as Icons”, silence, and silent expectation, are themselves “reverence for words and the truth which the reveal.”